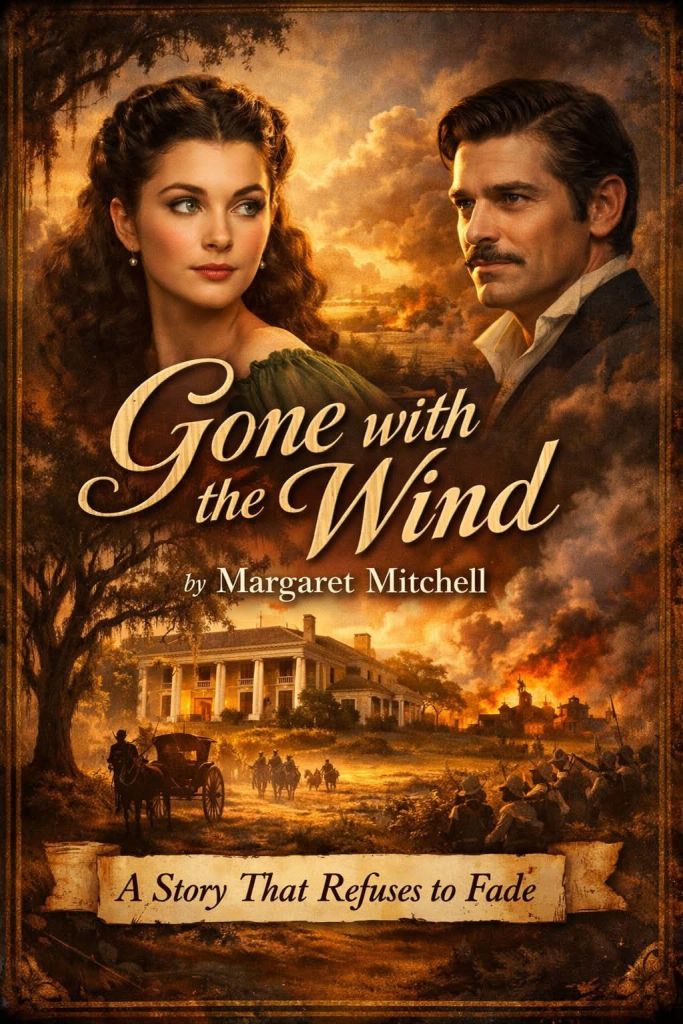

Gone with the Wind — A Story That Refuses to Fade

There are novels we read, and then there are novels that linger—like a remembered voice, like the scent of a place we have never been to yet somehow miss. Gone with the Wind belongs to the second kind. Long after the final page is turned, something remains unsettled inside the reader, a quiet ache shaped by loss, longing, and resilience.

Set against the sweeping collapse of the American South during the Civil War, the novel does not merely tell a historical story—it inhabits time. The old world of wide verandas, cotton fields, and rigid social codes slips slowly through the fingers of its characters, and through ours. What begins as romance and grandeur gradually becomes survival, adaptation, and moral reckoning.

At the heart of it all stands Scarlett O’Hara—a character who refuses to behave as she should, or feel as she is expected to. She is selfish, courageous, vain, tireless, blind, and brilliant—sometimes all at once. Her determination to survive, no matter the cost, gives the novel its pulse. Scarlett is not designed to be loved easily; she is designed to be remembered. Through her, the novel quietly asks an uncomfortable question: Is survival a virtue, even when it hardens the soul?

What makes the novel unforgettable is how gently its analysis unfolds beneath the narrative. The war does not arrive as a heroic spectacle; it creeps in as absence—empty houses, ruined fields, unreturned men. The romantic ideals of honor and gallantry are steadily dismantled, replaced by hunger, fatigue, and moral compromise. The South’s illusion of permanence dissolves, and with it, the illusion that love alone can sustain a life.

Then there is Rhett Butler, standing slightly apart from the world he understands too well. Cynical yet tender, amused yet wounded, Rhett sees the coming collapse long before it arrives. His love for Scarlett is not idealized; it is strained, wounded, and painfully human. Their relationship is not a fairytale—it is a study in misrecognition, timing, and emotional blindness. They love each other deeply, yet never at the same moment, never in the same way.

Perhaps that is why the novel leaves such a void when it ends. There is no comforting closure, no moral neatness. Instead, there is endurance. The famous ending does not offer certainty—it offers hope postponed. Tomorrow becomes a fragile promise rather than a guarantee.

What Gone with the Wind ultimately captures is the tragedy of change—not just historical change, but personal change. People grow, but not always wisely. Societies fall, but not without leaving ghosts behind. Love survives, but sometimes too late to save what mattered most.

To read this novel is to sit quietly with impermanence. It reminds us that the past is never truly gone—it shapes us, burdens us, and sometimes blinds us. And when the story ends, one feels an odd, hollow silence, as if something vast has moved on, taking its certainty with it.

Perhaps that is why readers return to it again and again—not to relive the romance, but to understand the loss.

And maybe, like Scarlett, we close the book telling ourselves: Tomorrow… we will think about it.

Credit:English Literature, Facebook